Frequency and Causes

The Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) is an inherited heart disease, which appears mostly in big dog breeds. It is a myocardial insufficiency which cannot be healed and its lethal progression can only be delayed with medication. The DCM and the sudden cardiac death (which is in most cases directly connected to the DCM, see below) is one of the most frequent causes of death in great danes with 20%- 35% (depending on the data collection and colour).

By now there exist severeal studies and data collections worldwide about the DCM in great danes. Dr. Kresken (head of the Collegium Cardiologicum in Germany) examined 397 great danes in a period of several years, out of which 31% had a heart issue. He presented the results of his data collection on the VDH (German Kennel Club) congress “Experten Erklären” in Düsseldorf in 2012. Excerpts of his presentation and an interview with Dr. Kresken can be found in the following information film about DCM in Danes by Ruth Stolzewski from 2012:

In the same year a study by Stephenson et al. (2012) was published in the Journal for Vet. Intern. Med. For this study 103 great danes older than 4 years, which were considered healthy by their owners, were examined. Only 27% of the dogs were younger than 6 years and the prevalence of DCM was 35,9%!

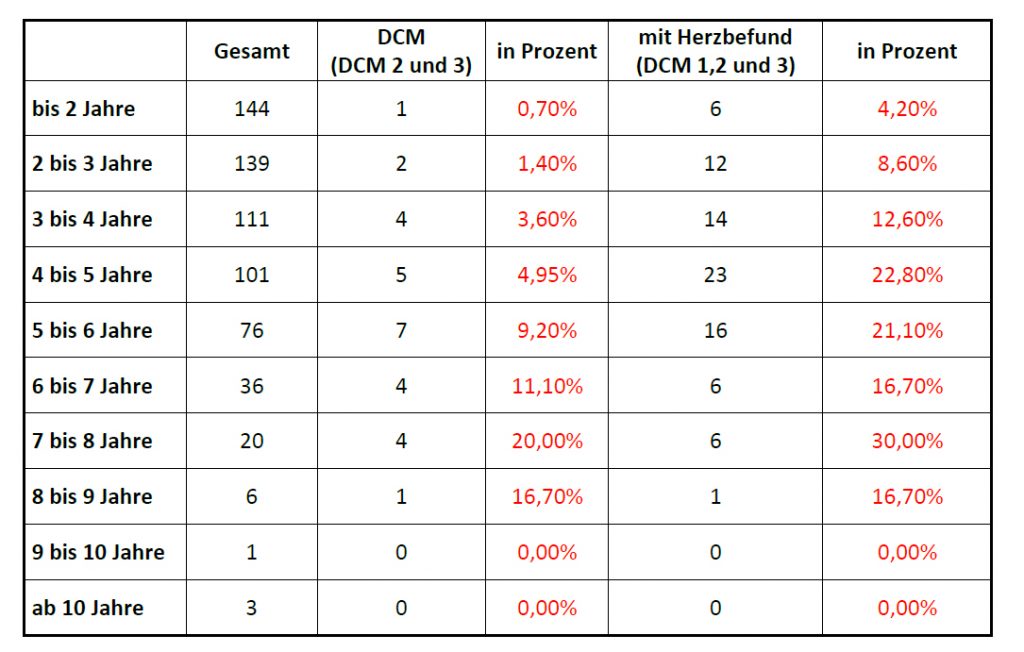

Also in the Deutscher Doggen Club (DDC) all breeding dogs had to be heart screened with an ultrasound and ECG in the scope of the so-called “DCM-study” from 2014-2016. Unfortunately this data collection has not been evaluated in a scientific study yet (february 2019).

Furthermore mostly young dogs had been examined. But since the DCM is a disease which develops in the course of the lifetime, mostly between 3 and 6 years, the results are distorted: 13,185 of the 565 examined danes with an average age of only 3,6 years had a suspicious finding (DCM 1, 2 or 3), out of which 4,39% had subclinical or clinical DCM. But only 10,35% of the dogs examined in the DDC were older than 6 years, the age in which a dog can only be diagnosed healthy or diseased with certainty. If you look at the prevalence in the different age groups it can be noticed, that the frequency of DCM raises with age and 20% of danes between 7 and 8 years have subclinical or clinical DCM (DCM 2 and 3), and even 30% have a suspicious finding (DCM 1, 2 and 3).

But despite this high numbers the heart ultrasound is not mandatory neither in the DDC nor in the second German Breed Club for great danes, the KyDD (Kynologische Gesellschaft für Deutsche Doggen). The president and the head of the breeding committee of the DDC even describe the mandatory heart screening as “patronizing” in the proverb of the studbook 2017.

In some European breed clubs the heart ultrasound is already mandatory, for example in the Netherlands it has to be performed yearly, in Austria every two years, and in Finnland it will be mandatory starting from July 2019 once per year.

It is interesting, that at least in continental Europe the blue colour group is much more affected of DCM than fawn/brindle and black/harle. This might be an indication for a high heratibility of this disesase. The different prevalences by colour group probably originate from popular sires which had been frequently used in the past and spread the defective genes.

Males are more often affected with DCM and the disease shows a more aggressive progression.Praxis der Kardiologie, Dr. Kresken et al. Enke Verlag 2017

Because of this fact an X-chromosomal inheritance had been predicted for the DCM for a while, but right now most scientists suggest a polygenetic mode of inheritance, which means that many genes are responsible for the development of DCM. That’s why it is very difficult to develop a gene test. But a gene test would be very important to identify carriers, which means animals who are healthy in the phenotype, but still can pass on the disease to their offspring. According to the prevalence of the DCM in the great dane population one can suggest, that up to three quarters of individuals carry defective genes (according to the Hardy-Weinberg-rule, Rassehundezucht Genetik für Züchter und Halter – Irene Sommerfeld-Stur, Müller Rüschlikon Verlag, 2016). This is why the Association for Healthy Great Danes has started a research project to develop a gene test in cooperation with the Veterinary University in Hanover/Germany and supports it logistically and financially.

What happens when a dog has DCM and how can you recognize it?

There are two types of DCM, the so-called “wavy-fiber-type” (Type 1) and the “fatty-infiltrated-type” (Type 2). When a dog has DCM the fibers of the heart muscle start to dissolve, in the “wavy-fiber-type” they dissolve in wave-shape, in the “fatty-infiltrated-type” fat cells are embedded between the fibers. Type 1 is frequent in great danes, type 2 appears regularly. (Praxis der Kardiologie, Dr. Kresken et al. Enke Verlag 2017)

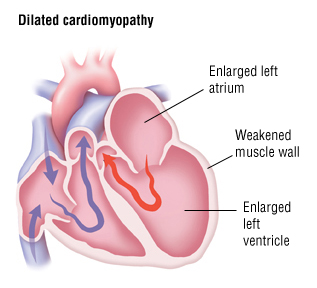

In both types there is a long phase, in which one cannot recognize any symptoms, the so-called “cellular phase”, in which the heart muscle starts to dissolve. In the so-called “subclinical” or “occult” phase the DCM cannot be recognized by the dog owner, but it can be detected with a heart ultrasound and ECK by a specialized cardiologist. In the “clinical” phase also the dog owner is able to recognize symptoms like performance problems, coughing, Dyspnoe, fainting, a blue tongue and other signs of a shortage of oxygen. In type 1 of the DCM a dilation of the left ventricle and a decline of the pumping power of the heart can be detected in the ultrasound.

In type 2, which is also called arhythmogenic DCM or Doberman DCM there cannot be detected any changes of the heart in the ultrasound at first place, but the ECG will show arhythmias of the heart beat. The only visible symptom of this type of DCM is quite often the sudden cardiac death, which means the dog dies because his heart beat just stops for too long. This is a frequent cause of death in great danes.

If the DCM is diagnosed at an early stage its progression can be slowed down with medication. The rate of survival is quite different and depends on the progression and stage of the disease. Some dogs survive only a few months, others a few years.

It is advisable for great dane owners to have an ultrasound (and ECG) performed of their dogs as a precaution starting from the age of one year and then at least every two years. The examination should be performed by a specialist cardiologist and not only by a normal veterinarian.

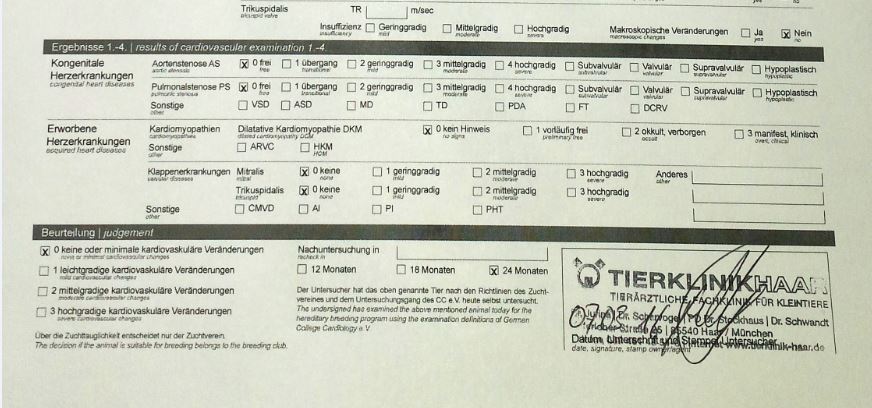

The examination starts with an ausculation of the heart. Then the heart ultrasound is performed with an short-term ECG. The dog will be diagnosed “free of DCM” (DCM 0 in the German Collegium Cardiologicum, CC) when it doesn’t show any signs of DCM. It will be diagnosed “equivocal” (DCM 1) when there are a few light symptoms of DCM detectable. A dog like this should be screened every 6-12 months to see if a DCM will develop. Subcinical (preclinical)/occult DCM (DCM 2) will be diagnosed if the dog shows clear symptoms of a DCM in the ultrasound and ECG, but not from outside and DCM 3 means clinical DCM, which means the dog is in the final phase of the disease and its survival rate is very low.

When arhythmias of the heart beat are detected in the ECG it depends on the shape and frequency of them if they are dangerous and have to be treated or if they are harmless.

Single VES (Ventricular Extrasystols) can also appear in a healthy organism. Up to 50 VES/day can be normal in a dog.

Praxis der Kardiologie, Dr. Kresken et al. Enke Verlag 2017

The different types of extrasystols are categorized depending on the risk of a sudden cardiac death. Single, monomorphe extra heart beats are the least risky, and the more extra beats follow each other, and the more often they appear the higher is the risk. Not all heart arhythmias are caused cardially – which means by the hart. There are also several non-cardial reasons like stomach torsion, sepsis, trauma, tumors, pain, fever, imbalance of elektrolytes etc. To define the exact shape and cause of the arhythmias it is advisable to perform other examinations like a blood test or a 24h ECG.

Experience report

My great dane male Ludwig was diagnosed with DCM at the age of 8,5 years – so quite late. He was otherwise still fit except for some signs of old age. First he got only one heart medication – Vetmedin – but his condition deteriorated quickly. Only 3 months after diagnosis he started to vomit water, which had accumulated in his lungs, because his heart didn’t pump strong enough anymore. I went to the cardiologist again and from now on Ludwig got 13 pills a day from 4 different medications. But this also didn’t help.

One night I had to call an emergency vet to come to my home, because Ludwig almost suffocated. It was terrible to see your dog fighting to breath and not being able to help. The vet injected a medication for dehydration which helped for the moment. But I promised to Ludwig and to myself, that I am going to release him the next time this will happen. I got a lot of advises from other DCM-affected dog owners, one of them was to get myself an dehydration injection fromy my vet for the case of emergency, to at least stop the suffering in that moment. The worst thing was, that during the day Ludwig seemed quite agile – if it wasn’t too hot – and that he was mentally and locomotory still very fit. This is why the decision to let him go was very very difficult. And I also hoped that his condition would stabilize with all the medication he got. But in the morning of the 27.07.2016 he was again vomiting huge amounts of water from his lungs. He was struggling to breath and I could see the panic in his eyes. So I injected the dehydration medication and called the animal hospital and a good friend to accompany during this very last step. Ludwig fell asleep in my arms. I will never forget his very last deep breath. On one hand I am glad I could be with him in this moment and he didn’t have to suffer. On the other hand I am still thinking about if it was the right moment to let him go. Well I guess there is never the “perfect moment” to say goodbye to your best friend who accompanied you every single day in 9 years.

A report by Ruth Stolzewski